• Latin digraphs - consonants : See my notes on:

bh

RBM-rule3.htm

by U Kyaw Tun, M.S. (I.P.S.T., U.S.A.), Daw Khin Wutyi, B.Sc., and staff of Tun Institute of Learning (TIL). Not for sale. No copyright. Free for everyone. Prepared for students and staff of TIL Research Station, Yangon, MYANMAR : http://www.tuninst.net , www.romabama.blogspot.com

index.htm |

Top

RBM-rules-indx.htm

Rule 03. - consonants

01. BEPS consonants and vowels

02.

Graphemes with regular English consonants:

b B,

c, d D, ð Ð,

f,

g G, gn/ng,

h hk hp

hs ht HT,

j, k

kS, l ,

m, n, N, ñ,

Ñ,

p, q, r,

s, S, sh,

t,

T, v

, w, x, y, z,

Z

UKT notes

• Latin digraphs - consonants

: See my notes on:

bh

![]() {va.}

; <gh> Mon-Myan

{va.}

; <gh> Mon-Myan

![]() {hké}

{hké}

-- UKT 150408, 151212, 200812

Diacritics and other suitable signs are introduced to reflect the pronunciation. Diacritics in Romabama are chosen in a way so that even if a diacritic is lost, the effect would be minimal. As for digraphs, I try not to use them, unless it is absolutely necessary.

Note the presence of lisping consonants

used for Eng-Lat & Skt-Dev such as:

![]() {S~ma.} ष्म ,

{S~ma.} ष्म ,

![]() {S~la.} ष्ल, and

{S~la.} ष्ल, and

![]() {S~ka.} ष्क in the BEPS

basic consonants.

{S~ka.} ष्क in the BEPS

basic consonants.

"A lisp, also known as sigmatism, is a speech impediment in which a person misarticulates sibilants ([s],[z],[ts],[dz]),([ʒ],[ʃ], [tʃ], [dʒ]). [1] These misarticulations often result in unclear speech."

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lisp 151212

Note that "digraphs" (showing two

glyphs in tandem) and "diphthongs"

(showing the approximate pronunciation of

a vowel) are entirely different. Diphthongs

and Triphthongs are common in English, and

what the Westerners had thought to be

Diphthongs or Triphthongs in Bur-Myan are

Monophthongs without any "glide" in

pronunciation. The fact that typical English

diphthongs such as <boy> and <cow>

are commonly pronounced as

![]() {Bweín:} and

{Bweín:} and

![]() {kaún:} by Bur-Myan speakers (including

myself at one time) shows that there are

no diphthongs in Burmese.

{kaún:} by Bur-Myan speakers (including

myself at one time) shows that there are

no diphthongs in Burmese.

For many terms in Bur-Myan, consult

Burmese Grammar and Grammatical Analysis 1899

by A. W. Lonsdale, Rangoon: British Burma Press,

1899 xii, 461, in two parts. Part 1.

Orthoepy and orthography; Part 2. Accidence

and syntax,

and proceed to Part 1. Orthoepy and orthography,

The sounds of letters .

Follow the navigation:

BurMyan-indx.htm >

BG1899-indx.htm >

BG1899-1-indx.htm

> Vowels ch03-1.htm

and

Consonants -- ch03-2.htm

(link chk 151222)

- UKT 150412, 150810

ß is U00D7 or Alt+0223 . See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C3%9F 150810

- though known as "Latin Small Letter Sharp S", because of its shape which looks alike "Cap B", I have tentatively chosen it to represent Mon-Myan{ßa.} and

{ßé}.

The phoneme /b/ was probably not present in Skt-Dev,

because the Skt-Dev akshara is clearly invented

from akshara

![]() {wa.} just as in the case of /v/.

See grapheme: v .

{wa.} just as in the case of /v/.

See grapheme: v .

{wa.} व + diagonal line -->

{ba.} ब

With the inclusion of Mon-Myan, Romabama needs

2 additional glyphs for Consonantal Row#7, to

represent sounds similar to /b/. I have

tentatively identified the 5 sounds of Row#7 as

![]() {ha.}

{ha.}

![]() {La.}

{La.}

![]() {ßa.}

{ßa.}

![]() {a.}

{a.}

![]() {ßé}

{ßé}

UKT 200813: This phoneme has been called the aspirate of /b/ and written as भ «bha»

in Skt-Dev. Though Mon-Myan uses the same glyph

![]() ,

it is pronounced as

,

it is pronounced as

![]() {hpé} in Mon-Myan.

{hpé} in Mon-Myan.

• ð (Alt0240) (Latin small letter Eth)

in row-3 akshara

![]() {ða.} : [UKT 150410:

bookmark for

{ða.} : [UKT 150410:

bookmark for

![]() {ða.} - d3a1 ]

{ða.} - d3a1 ]

(Caution: the vd-pronunciation of

English-Latin <þ>/<th> is

also given as /ð/)

• Ð (Alt0208) (Latin cap letter Eth)

for row-3 akshara

![]() {Ða.} : [UKT 150410: bookmark for

{Ða.} : [UKT 150410: bookmark for

![]() {Ða.} - DD3a1 ]

{Ða.} - DD3a1 ]

See also v

• Labio-dental sounds, /f/ and /v/ are missing in Bur-Myan. It is also possible that they were absent in Vedic in days before Panini formalization of Védic (Tib-Bur) into Classical Sanskrit (IE). Now that Romabama is to be used for BEPS (Burmese-English-Pali-Sanskrit speeches), there is a need to invent new glyphs from the nearest existing ones:

{fa.} from

{hpa.} फ

{va.} from

{ba.} ब (derived from

{wa.} व /w/ )

The process of creating new glyphs from the

nearest existing ones seems to be a regular

process when one Akshara-syllable language has

to be transcribed into another. Because I am

a Tib-Bur speaker, I have chosen my source

aksharas from the bi-Labials. In U Hoke Sein

PMD pages

![]() {hsa.} &

{hsa.} &

![]() {za.}, we see what I take to be examples for

this process.

{za.}, we see what I take to be examples for

this process.

I've come to realized that Bur-Myan phonology and that of Mon-Myan is entirely

different even though the same Myanmar akshara is used. For regular Bur-Myan

{ka.}, {hka.}, {ga.}, {Ga.}, {gna.}, Mon-Myan has:

-

![]() {ka.},

{ka.},

![]() {hka.},

{hka.},

![]() {gé}*, {hké}*, {n~ré}* -

bk-cndl-{ka.}-row<))

{gé}*, {hké}*, {n~ré}* -

bk-cndl-{ka.}-row<))

Listen carefully, and you'll hear

![]() {gé}, but, {hké} in place of Bur-Myan {Ga.} . Remember what you are hearing

the Martaban dialect of Mon-Myan. However, it is clearly stated by foreign

observers that there is no /g/ sound in Peguan dialect - the dialect of

Hanthawaddy Kingdom with capital in Pegu. See: # Grammatical notes and Vocabulary

of the Peguan Language,

by J.M. Haswell, Rangoon, American Mission Press, 1874

{gé}, but, {hké} in place of Bur-Myan {Ga.} . Remember what you are hearing

the Martaban dialect of Mon-Myan. However, it is clearly stated by foreign

observers that there is no /g/ sound in Peguan dialect - the dialect of

Hanthawaddy Kingdom with capital in Pegu. See: # Grammatical notes and Vocabulary

of the Peguan Language,

by J.M. Haswell, Rangoon, American Mission Press, 1874

-

MV1874-indx (link chk 200813) - in TIL HD-PDF and SD-PDF libraries

- JMHaswell-PeguanGrammVocab<Ô> /

Bkp<Ô> (link chk 200813)

and # Notes on the transliteration of Burmese

alphabet into Roman characters, and vocal and

consonantal sounds of the Peguan or Talaing

language, by R.C. Temple, Rangoon 1876,

in TIL HD-PDF and SD-PDF libraries

- RCTemple-Translit-Bur<Ô> 1876 /

Bkp<Ô> (link chk 200813)

UKT 200820: Every Bur-Myan Buddhist males of my generation, and before, had to enter the Buddhist monk-hood - at least temporarily twice - in life. We were taught how to pronounce this phoneme with a deep guttural sound, which I've named deep-H. The first row Myanmar akshara matrix reads:

Bur-Myan:

{ka.},

{hka.},

{ga.},

{Ga.},

{gna.}

Mon-Myan, Peguan dialect: {ka.}, {hka.}, {ké}, {hké}, {gné}

After learning Mon-Myan, I have to change my view - there is no deep-H in Mon-Myan: what it has is an aspirate similar to Skt-Dev घ «gha». See my note on <gh>

Finding that there is no /g/ sound has prompted me to transcribe r1c5 as:

![]() {gna.}/

{gna.}/

![]() {ng},

{ng},

which reminds me of the two English words: <sing> and <sign> both described as

ending in nasal sounds. My question is on the exchange of places of <n>

and <g>.

• hiän (hi + Alt0228} - a difficult and controversial vowel is met in

Pal-Myan

![]() {ta.hiän}.

See UHS PMD0436

{ta.hiän}.

See UHS PMD0436

The Dot-above

![]() {þé:þé:tín} is

{þé:þé:tín} is

![]() {ng} in the Kinsi-form:

{ng} in the Kinsi-form:

![]() .

.

UKT 200814: Of the 5 c2 wag consonants, r1c2 is the only one which has been commonly transcribed as kh which I'm obliged to change to hk

- UKT 150420, 200813

Superficially speaking, there should have been

no transcription difficulty in Bur-Myan

![]() {ka.}

into English, unless you notice that the

IE speakers (English) cannot differentiate

{ka.}

into English, unless you notice that the

IE speakers (English) cannot differentiate

![]() {hka.} from

{hka.} from

![]() {ka.}. They could only hear them as "allophones" of /k/. However on narrow

transcription IPA has to show the difference as

{ka.}. They could only hear them as "allophones" of /k/. However on narrow

transcription IPA has to show the difference as

![]() {ka.} = [k], and

{ka.} = [k], and

![]() {hka.} = [kʰ].

{hka.} = [kʰ].

In transcription and pronunciation of

English words like <skin> into Bur-Myan,

the <sk> is found to be difficult,

because the <s> in <sk> is an

unknown phoneme in Bur-Myan. It is not

palatal plosive-stop

![]() {sa.} च but dental hissing fricative

{sa.} च but dental hissing fricative

![]() {Sa.} ष.

{Sa.} ष.

Remember to differentiate

{sa.} च ,

{c} च्

{Sa.} ष ,

{S} ष्

This has given rise to another class of consonants not found in Bur-Myan:

{S~ka.},

{S~ta.},

{S~pa.}

And in <skin>, <sk> is

![]() {S~ka.} ष्क (shortened to {Ska.}).

We must not forget about Skt-Dev Pseudo-Kha

{S~ka.} ष्क (shortened to {Ska.}).

We must not forget about Skt-Dev Pseudo-Kha

![]() {kSa.} (1 eye-blnk), and,

{kSa.} (1 eye-blnk), and,

![]() {kSa} (2 blnk). {kSa.} & {kSa} can be alternatively written as {ksa.} & {ksa}

{kSa} (2 blnk). {kSa.} & {kSa} can be alternatively written as {ksa.} & {ksa}

But, remember: Pseudo-Kha

{kSa.} क्ष is derived from क ् ष

whereas, Lisping-Ska is from ष ् क

The Skt-Dev क्ष conjunct is fairly important in Sanskrit

language. It is more important than Kha

![]() {hka.} ख

because of which I have been calling it Pseudo-Kha

{hka.} ख

because of which I have been calling it Pseudo-Kha

![]() {kSa.} क्ष . See A Practical Sanskrit

dictionary by A. A. Macdonell, (in Skt

-Dev) 1893:

{kSa.} क्ष . See A Practical Sanskrit

dictionary by A. A. Macdonell, (in Skt

-Dev) 1893:

-

MC-indx.htm >

MCpp-indx.htm >

and go to

![]() MC077F.htm

MC077F.htm

![]() MC078.htm

MC078.htm

![]() MCH79-1.htm for

Pseudo-Kha

MCH79-1.htm for

Pseudo-Kha

![]() {kSa.} क्ष

{kSa.} क्ष

and,

![]() MC079-2.htm

MC079-2.htm

![]() Nep* MC079-2B.htm

Nep* MC079-2B.htm

![]() MC080.htm for

Regular Kha

MC080.htm for

Regular Kha

![]() {hka.} ख

{hka.} ख

Go further into Skt-Dev, when we find words like • अस्खलित [ a-skhalita ] 'uninterrupted', 'unhindered' , 'not coming to a standstill' , when we have to deal with {S~hka.}. The <h>, here, can be a problem. Because of that, there is a need to introduce {Ka.} to represent {hka.}. Then we can have {SKa.}. See: - Romabama-rule2.htm for Differentiation of capital and small letters to extend English alphabet

See also in entry on letter S .

UKT 181120: Wikipedia:

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Latin-script_digraphs#L 181119

"〈lh〉, in Occitan, Gallo, and Portuguese, represents a palatal lateral approximant /ʎ/. In many Indigenous languages of the Americas it represents a voiceless alveolar lateral fricative /ɬ/."

Also, see UKT notes below for vowels.

The Bur-Myan akshara

![]() {la.} is difficult for speakers

of many languages. After coming across highly rhotic

{la.} is difficult for speakers

of many languages. After coming across highly rhotic

![]() {iRRi.} in Skt-Dev, slightly rhotic

{iRRi.} in Skt-Dev, slightly rhotic

![]() {iRi.} in Pal-Myan, and non-rhotic Raric

{iRi.} in Pal-Myan, and non-rhotic Raric

{ra.ric}-sound in Bur-Myan, I realized that the BEPS

vowels must be represented on a 3-dimensional graph.

Unless, I do this, I cannot explain satisfactory to

myself about the difficulty of pronouncing the phonemes

![]() {la.},

{la.},

![]() {lha.},

{lha.},

![]() {lya.},

{lya.},

![]() {lhé} etc.

{lhé} etc.

The counter-part of highly rhotic

![]() {iRRi.} is

{iRRi.} is

![]() {iLLi} in Skt-Dev.

{iLLi} in Skt-Dev.

UKT 200816: Letter n or syllable

![]() {na.}/

{na.}/

{n} either in the onset or in the coda presents no difficulty. However when the

letter n is used to represent other phonemes not present in English, we

ran into misunderstandings. Letter n has been used in digraphs

ng to represent r1c5 /ŋ/

{ng.}

{ng}

{ng:}

ny to represent palatal affricate r2c5 /ɲ/{ña.}

{ña}

{ña:}

while palatal stopwhich occupies r2c5 in Myanmar akshara matrix has been lost:

to remedy which I've moved it into palatal approximant position

The phoneme /n/ is the first in which I've found out that Wicsa is used differently in Skt-Dev and Mon-Myan.

{na:.} नः (1/2 blk),

{na.} न (1 blk),

{na} ना (2 blk),

{na:} (2 blk + emphasis)

The equivalent of Mon-Myan & Skt-Dev{na:.} नः in Bur-Myan is

{naa.} - the vowel-duration is 1/2 blk.

UKT 200816:

The letter ñ (Alt0241) (Latin small letter N with Tilde) is used

for Nya-minor

![]() {ña.} corresponding to Eng-Lat digraph ny . However, remember the English digraph ny can also mean

{ña.} corresponding to Eng-Lat digraph ny . However, remember the English digraph ny can also mean

![]() {n~ya}

/nə.ja/ or

{n~ya}

/nə.ja/ or ![]()

![]() {na.ya.pïn.}

{na.ya.pïn.}

![]() {nya.}

. This shows that you must differentiate Nya-minor

{nya.}

. This shows that you must differentiate Nya-minor

![]() {ña.} from Na'ya'pin

{ña.} from Na'ya'pin

![]() {nya.} .

{nya.} .

{hkyiñ} - adj. sour; acid. v. turn sour; acid - MED2010-072

The capital letter Ñ (Alt0209) is used for

Nya-major

![]() {Ña.}: different from Nya-minor

{Ña.}: different from Nya-minor

![]() {ña.}. Nya-major is an important akshara in Bur-Myan. It is not just a

horizontal "conjunct" as Pali-scholars would like to present. If so, Nya-major

would have to break up under virama as

{ña.}. Nya-major is an important akshara in Bur-Myan. It is not just a

horizontal "conjunct" as Pali-scholars would like to present. If so, Nya-major

would have to break up under virama as

![]() ~

~![]() and become mute. It has to be preceded by an akshara, thus in Pali-Myan,

and become mute. It has to be preceded by an akshara, thus in Pali-Myan,

![]() {píñ~ña} "education".

{píñ~ña} "education".

I'll repeat Nya-major is an important akshara in Bur-Myan:

{Ña.} /ɲa/ - n. night - MED2010-156

{ÆÑ.þæÑ} - guest - MED2010-625

{Zé:þæÑ} - n. shopkeeper, bazaar seller - MED2006-155

{Zé:þèý} - same as

{Zé:þæÑ} : not listed by MLC - UKT130817

{Zé:þèý} &

{Zé:wèý} : commonly used in Mandalay during our stay in

Mandalay Arts & Sc. Univ. , for bazaar "seller" and "buyer" - UKT13817

{præÑ} /prji/ - n. ¹. country. ². royal city. ³. abode - MED2006-289

{þæÑ} /thi/ - ¹. particle suffix -- MED2006-515

{þèý} - v. to carry, transport - MED2006-521

The problem of

![]() {ña.} &

{ña.} &

![]() {Ña.} vying for cell r2c5 is solved when

the former is identified as a nasal, and

the latter to be an approximant of the

same palatal group. This necessitates

{Ña.} vying for cell r2c5 is solved when

the former is identified as a nasal, and

the latter to be an approximant of the

same palatal group. This necessitates

![]() {ya.} /j/ to be moved to velar group.

{ya.} /j/ to be moved to velar group.

One argument in favour of moving

![]() {ya.} to velar lies in the idea that Myanmar

akshara was well thought out by the

designer, who had simply flipped

{ya.} to velar lies in the idea that Myanmar

akshara was well thought out by the

designer, who had simply flipped

![]() {ka.} (at the top of the column) to get

{ka.} (at the top of the column) to get

![]() {ya.} (the approximant). Both are in the same column - the Velars. However,

flipping

{ya.} (the approximant). Both are in the same column - the Velars. However,

flipping

![]() {pa.} (at the top of the Bilabial column) does not give the approximant as

{pa.} (at the top of the Bilabial column) does not give the approximant as

![]() {ga.}. It gives

{ga.}. It gives

![]() {wa.}.

{wa.}.

UKT 200816:

In Bur-Myan there are two semi-consonants,

which are known in other languages as

semi-vowels. They are

Ya

In Bur-Myan there are two semi-consonants,

which are known in other languages as

semi-vowels. They are

Ya

![]() {ya.} /j/ and Ra

{ya.} /j/ and Ra

![]() {ra.} /ɹ/ . Both are non-rhotic,

but in Rakhine dialect of Bur-Myan,

{ra.} /ɹ/ . Both are non-rhotic,

but in Rakhine dialect of Bur-Myan,

![]() {ra.} becomes slightly rhotic. In Pali-Myan, Ra becomes more rhotic,

because of which I would like to transcribe it as

{ra.} becomes slightly rhotic. In Pali-Myan, Ra becomes more rhotic,

because of which I would like to transcribe it as

![]() {Ra.}. However, it not to be because the glyph

{Ra.}. However, it not to be because the glyph

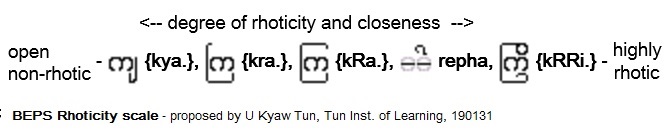

![]() would have to remain the same. In Skt-Myan, derived from Skt-Dev, Ra becomes

more rhotic. To show this rhoticity, I've defined a scale as shown.

would have to remain the same. In Skt-Myan, derived from Skt-Dev, Ra becomes

more rhotic. To show this rhoticity, I've defined a scale as shown.

Ya and Ra are

classified by IPA as fricative-approximants,

and in akshara languages they are named

![]()

![]() {a.wag} "non-classifiable", and are in row#6 of the Myanmar

akshara.

{a.wag} "non-classifiable", and are in row#6 of the Myanmar

akshara.

They also belong to the class of Bur-Myan medial-formers, and give rise to

![]() {ya.pín.} and

{ya.pín.} and

![]() {ra.ric}. They can be modified selectively by other medial-formers. When Ya

and Ra are modified by medial-former

{ra.ric}. They can be modified selectively by other medial-formers. When Ya

and Ra are modified by medial-former

![]() {ha.} into

{ha.} into

![]() {ha.hto:}, their pronunciation

becomes definitely hissing-sibilant

similar to IPA /ʃ/. Because of this

MLC uses both of them to represent

/ʃ/. Romabama has to name them as

{ha.hto:}, their pronunciation

becomes definitely hissing-sibilant

similar to IPA /ʃ/. Because of this

MLC uses both of them to represent

/ʃ/. Romabama has to name them as

![]() {yha} &

{yha} &

![]() {rha}.

{rha}.

UKT 200816:

We have only palatal plosive-stop, r2c1

![]() {sa.}/

{sa.}/![]() {c} , and so dental hissing fricative

{c} , and so dental hissing fricative

![]() {Sa.}/

{Sa.}/

![]() {S}, has to be invented for words imported from Eng-Lat and Skt-Dev. Even when IE speakers speak of the r2 consonants in their inventory, what they have

are actually palatal affricates. However not to make our discussion more

complicated, we will ignore the presence

of affricates for the present.

{S}, has to be invented for words imported from Eng-Lat and Skt-Dev. Even when IE speakers speak of the r2 consonants in their inventory, what they have

are actually palatal affricates. However not to make our discussion more

complicated, we will ignore the presence

of affricates for the present.

UKT 150409: Though same glyph is used in Bur-Myan,

{sa.}-palatal and

{Sa.}-dental, I have different glyphs in AK subfolder. They are associated with with killed-forms,

{c} and

{S}. And we have:

{sa.} च ,

{c} च्

{Sa.} ष ,

{S} ष्

Romabama spells English

<kiss> as

![]() {kiS} with a hissing sound at the end.

Do not spell it as

{kiS} with a hissing sound at the end.

Do not spell it as

![]() {kic} "to steal" because it will end with a stop.

The English word <Miss> is

{kic} "to steal" because it will end with a stop.

The English word <Miss> is

![]() {miS} not

{miS} not

![]() {mic}.

{mic}.

This dental-hissing phoneme is not present both in Bur-Myan and Pali-Myan. I became

aware of this

![]() {Sa.}/

{Sa.}/

![]() {S} and its derivative

{S} and its derivative

![]() {kSa.} क्ष --> क ् ष in my early days of studying Skt-Dev, when I came across Pseudo-Kha

{kSa.} क्ष --> क ् ष in my early days of studying Skt-Dev, when I came across Pseudo-Kha

![]() {kSa.} क्ष --> क ् ष . Both are unknown also in Pali-Myan which has, like

Bur-Myan, Regular-Kha

{kSa.} क्ष --> क ् ष . Both are unknown also in Pali-Myan which has, like

Bur-Myan, Regular-Kha

![]() {hka.} only.

{hka.} only.

Being a conjunct

![]() {kSa.} क्ष is mute, but Skt-Dev speakers, insert a schwa after

k and pronounce it as /kəsa/. Of course

{kSa.} क्ष is mute, but Skt-Dev speakers, insert a schwa after

k and pronounce it as /kəsa/. Of course

![]() {kSa.} क्ष breaks up under a virama.

{kSa.} क्ष breaks up under a virama.

The second time I became aware of the dental-hisser is in the study of English

lisping consonants such as

![]() {Ska.} present in <skin>,

{Ska.} present in <skin>,

![]() {Sta.} present in <stink>, and

{Sta.} present in <stink>, and

![]() {Spa.} present in <spin>. In Skt-Dev, the dental-hisser is present in words like

Sri Ksetra

{Spa.} present in <spin>. In Skt-Dev, the dental-hisser is present in words like

Sri Ksetra

![]()

![]() {þa.ré hket~ti.ra} the name of an ancient capital city in Burma, and Ksatriya क्षत्रिय

= क ् ष त ् र ि य equiv. to

{þa.ré hket~ti.ra} the name of an ancient capital city in Burma, and Ksatriya क्षत्रिय

= क ् ष त ् र ि य equiv. to ![]() {hkût~ti.ya.} the ruling class

to which Gaudama Buddha had belonged.

{hkût~ti.ya.} the ruling class

to which Gaudama Buddha had belonged.

See also entry on kS .

- UKT 150412, 200817

Skt-Dev akshara श

«sha» can be killed without breaking up as

श् . This phoneme is spelled in

Bur-Myan either as

![]() {þhya.} or

{þhya.} or

![]() {rha.} as medials. Since a medial in Bur-Myan

will also break up under a virama {a.þût}, I have

to invent a new glyph:

{rha.} as medials. Since a medial in Bur-Myan

will also break up under a virama {a.þût}, I have

to invent a new glyph:

We have only palatal plosive-stop

{sa.}, and so dental hissing dental-fricative

{Sa.} is invented. Then,

{Sa.} +

{ha.hto:} -->

{sha.}

Note: Though

![]() {sa.} &

{sa.} &

![]() {Sa.} use the same glyph, the former is

the palatal plosive-stop, and the latter

the dental hissing-approximant. However,

the two are represented differently in

the coda:

{Sa.} use the same glyph, the former is

the palatal plosive-stop, and the latter

the dental hissing-approximant. However,

the two are represented differently in

the coda:

![]() {c} &

{c} &

![]() {S}.

{S}.

We note that MLC

![]() {rha.} with IPA /ɹ/ is easily

mistaken for /r/ with an R-sound. However,

{rha.} with IPA /ɹ/ is easily

mistaken for /r/ with an R-sound. However,

![]() {sha.} has no R-sound.

{sha.} has no R-sound.

See my comparison of Bur-Myan and Georgian-Mkhedruli in Romabama-rule1.htm

The combination of Georgian consonant t თ (consonant Letter Tan) and a ა (vowel Letter An) have Bur-Myan counter part

{ta.} which already has the basic vowel part as its inherent vowel.

თ + ა -->

{ta.}

- UKT 150412, 200820: See also letter b

• Labio-dental sounds, /f/ and /v/ are

missing in Bur-Myan. Now that Romabama

is to be used for BEPS

(Burmese-English-Pali-Sanskrit speeches),

there is a need to include graphemes to

represent these sounds in the Myanmar

script. Yet, I was very reluctant to

'invent' new written characters. I have

now no way out but to craft them out.

I have chosen

![]() {hpa.} and

{hpa.} and

![]() {ba.} the nearest to /f/ and /v/. Instead of

{ba.} the nearest to /f/ and /v/. Instead of

![]() {hpa.}, I should have chosen the tenuis

{hpa.}, I should have chosen the tenuis

![]() {pa.}, however, because of the absence of

the tenuis in English (unless preceded by

/s/), I have to use the voiceless-aspirate

{pa.}, however, because of the absence of

the tenuis in English (unless preceded by

/s/), I have to use the voiceless-aspirate

![]() {hpa.} with a (ha-hto:}.

{hpa.} with a (ha-hto:}.

And now Romabama is now representing

![]() {fa.} and

{fa.} and

![]() {va.} .

{va.} .

UKT 200819: The English-Latin letter w represents the

consonant-akshara with three pitch-registers in Bur-Myan:

![]() {wa.}

व ,

{wa.}

व ,

![]() {wa} वा ,

{wa} वा ,

![]() {wa:} --

{wa:} --

I've given the corresponding Skt-Dev aksharas. However it must be emphasized

that Bur-Myan and Pali-Myan aksharas are bi-labial approximants, whereas

Skt-Dev are labial-dental approximants. Actually I should have given:

![]() {va.}

व ,

{va.}

व ,

![]() {va} वा . The pronunciations of bi-labials and labial-dentals are very different

in our ears. However, it is beyond my ability to include "pronunciations" in my

comparison and I've no choice but to ignore it. See my notes in

RBM-rules-indx.htm

{va} वा . The pronunciations of bi-labials and labial-dentals are very different

in our ears. However, it is beyond my ability to include "pronunciations" in my

comparison and I've no choice but to ignore it. See my notes in

RBM-rules-indx.htm

and go to

• Comparison of Myanmar, Devanagari, and IPA ,

and

• Four vowel representation in Myanmar akshara

.

When we are young, we were taught that there are 5 vowels in English language:

a , e , i , o , u . And sometimes y is

also included citing the examples of English words like <by> and <my>, where

y is clearly a vowel. In a word like <you>, y is a starting-consonant

and u the ending-vowel. What about words like <cow> where "double-u"

is the ending-vowel. Now, double-u is simply w . In Bur-Myan <cow>

would be {kou} - where {ou} is the vowel. Bur-Myan has no such sound, but

Mon-Myan has:

![]() {ou}. When a Bur-Myan speaker has to pronounce <cow> he usually pronounces

{ou}. When a Bur-Myan speaker has to pronounce <cow> he usually pronounces

![]() {kaún:}. I hope, after learning BEPS languages, he would just say:

{kaún:}. I hope, after learning BEPS languages, he would just say:

![]() {kou} .

{kou} .

Personal note: I remember while staying, in 1975, in a rooming house in Bowral Street, Sydney, NSW, Australia, I'd difficulty in pronouncing my address. That was after of my staying in the US for two years, 1957-59 in Appleton, Wis., and after being corrected by my American classmates, I still could not properly produce my glides or semivowels.

"It is pointless to talk about letters. Semivowels are glides like /w/ and /j/ that act as part of a diphthong, so in conjunction with a vowel sound. ... So the words wet and yet are pronounced with a consonant glide at their fronts, and this is referred to as a semivowel because they start with a consonant sound. Dec 12, 2015" - Google search 200819

See also: vowel o

• ý (Alt0253) (Latin small letter Y with Acute)

for "killed {ya.}"

![]() {ya.þût}

{ya.þût}

{kèý-hsèý} - v. save; rescue - MED2010-024

The

![]() {ya.þût} is important to bring out the

difference in Bur-Myan "tones".

{ya.þût} is important to bring out the

difference in Bur-Myan "tones".

{kè.} (1 blk),

{kèý} (2 blk),

{kè:} (2 blk + emphasis)

- UKT 200812

From: Wikipedia:

1. - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Latin-script_digraphs 200817

2. - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Latin-script_trigraphs 200817

See my notes on digraphs in Romabama, taken from Wiki#1 Latin-digraphs .

Though I hate to use digraphs, which are often mistaken for diphthongs, I still have to use them in Romabama for consonants and vowels. I'm giving some of them taken from the following Wikipedia article

From: Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Latin-script_digraphs 200812

〈bb〉 is used in Pinyin for /b/ in languages such as Yi, where b stands for /p/. In English, doubling a letter indicates that the previous vowel is short (so bb represents /b/). In ISO romanized Korean, it is used for the fortis sound /p͈/, otherwise spelled 〈pp〉; an example is hobbang. In Hadza it is the rare ejective /pʼ/. In several African languages it is implosive /ɓ/. In Cypriot Arabic it is /bʱ/.

〈bh〉 is used in transcriptions of Indo-Aryan languages for a murmured voiced bilabial plosive (/bʱ/), and for equivalent sounds in other languages. In Juǀʼhoan, it's used for the similar prevoiced aspirated plosive /b͡pʰ/. In Irish orthography, it stands for the phonemes /w/ and /vʲ/, for example mo bhád /mə waːd̪ˠ/ ('my boat'), bheadh /vʲɛx/ ('would be'). In the orthography used in Guinea before 1985, 〈bh〉 was used in Pular (a Fula language) for the voiced bilabial implosive /ɓ/, whereas in Xhosa, Zulu, and Shona, 〈b〉 represents the implosive and 〈bh〉 represents the plosive /b/.

<bh> is used to derived a new phoneme

{va.} to handle the labial-dental Eng-Lat and Skt-Dev v the equivalent of

{wa.} in Bur-Myan and Pali-Myan. Go back <bh>

〈ch〉 is used in several languages. In English, it can represent /tʃ/, /k/, /ʃ/, /x/ or /h/. See article.

〈çh〉 is used in Manx Gaelic for /tʃ/, as a distinction from 〈ch〉 which is used for /x/.

〈čh〉 is used in Romani orthography and the Chechen Latin alphabet for /tʃʰ/. In the Ossete Latin alphabet, it was used for /tʃʼ/.

〈dh〉 is used in the Albanian alphabet, Swahili alphabet, and the orthography of the revived Cornish language [1] [3] [4] [5] for the voiced dental fricative /ð/. The first examples of this digraph are from the Oaths of Strasbourg, the earliest French text, where it denotes the same sound /ð/ developed mainly from intervocalic Latin -t-. [7] In early traditional Cornish 〈3〉 (yogh), and later 〈th〉, were used for this purpose. Edward Lhuyd is credited for introducing the grapheme to Cornish orthography in 1707 in his Archaeologia Britannica. In Irish orthography it represents the voiced velar fricative /ɣ/ or the voiced palatal approximant /j/; at the beginning of a word it shows the lenition of /d̪ˠ/, for example mo dhoras /mˠə ɣoɾˠəsˠ/ ('my door' cf. doras /d̪ˠorˠəsˠ/ 'door'). // In the pre-1985 orthography of Guinea, 〈dh〉 was used for the voiced alveolar implosive /ɗ/ in Pular, a Fula language. It is currently written 〈ɗ〉. In the orthography of Shona it is the opposite: 〈dh〉 represents /d/, and 〈d〉 /ɗ/. In the transcription of Australian Aboriginal languages, 〈dh〉 represents a dental stop, /t̪/. In addition, 〈dh〉 is used in various romanization systems. In transcriptions of Indo-Aryan languages, for example, it represents the murmured voiced dental plosive /d̪ʱ/, and for equivalent sounds in other languages. In Juǀʼhoan, it's used for the similar prevoiced aspirated plosive /d͡tʰ/. In the romanization of Arabic, it denotes 〈ﺫ〉, which represents /ð/ in Modern Standard Arabic.

〈fh〉 is used in Irish and Scottish Gaelic orthography for the lenition of 〈f〉. This happens to be silent, so that 〈fh〉 in Gaelic corresponds to no sound at all. For example, the Irish phrase cá fhad ('how long') is pronounced [kaː ad̪ˠ], where fhad is the lenited form of fad /fɑd/ ('long').

〈gh〉 is used in several languages. In English, it can be silent or represent /ɡ/ or /f/. See article.

<gh> Every Bur-Myan Buddhist males of my generation, and before, had to enter the Buddhist monk-hood - at least temporarily twice - in life. We were taught how to pronounce this phoneme with a deep guttural sound, which I've named deep-H. The first row Myanmar akshara matrix reads:

Bur-Myan:{ka.},

{hka.},

{ga.},

{Ga.},

{gna.} /ŋ/. However, in

Mon-Myan, Peguan dialect:{ka.},

{hka.},

{ké},

{hké},

{gné}

Note the extreme difference in r1c5,{gna.} and

{gné}. It is probably from Mon

that the Burmese had borrowed

/ɲ/ .

After learning Mon-Myan, I have to change my view - there is no deep-H in Mon-Myan: what it has is an aspirate similar to Skt-Dev घ «gha»

Go back gh-note-b

〈hh〉 is used in the Xhosa language to write the murmured glottal fricative /ɦ̤/, though this is often written h. In the Iraqw language, hh is the voiceless epiglottal fricative /ʜ/, and in Chipewyan it is a velar/uvular /χ/. In Esperanto orthography, it is an official surrogate of 〈ĥ〉, which represents /x/.

〈hj〉 is used in the Italian dialect of Albanian for /xʲ/. In Faroese, it represents either /tʃ/ or /j/. In Icelandic it is used to denote /ç/.

〈hl〉 is used for /ɬ/ or /l̥/ in various alphabets, such as the Romanized Popular Alphabet used to write Hmong (/ɬ/) and Icelandic (/l̥/). See also reduction of Old English /hl/.

〈hm〉 is used in the Romanized Popular Alphabet used to write Hmong, where it represents the sound /m̥/.

〈hn〉 is used in the Romanized Popular Alphabet used to write Hmong, where it represents the sound /n̥/. It is also used in Icelandic to denote the same phoneme. See also reduction of Old English /hn/.

〈hr〉 is used for /ɣ/ in Bouyei. In Icelandic it is used for /r̥/. See also reduction of Old English /hr/.

〈hs〉 is used in the Wade-Giles transcription of Mandarin Chinese for the sound /ɕ/, equivalent to Pinyin x.

〈hu〉 is used primarily in the Classical Nahuatl language, in which it represents the /w/ sound before a vowel; for example, Wikipedia in Nahuatl is written Huiquipedia. After a vowel, ⟨uh⟩ is used. In the Ossete Latin alphabet, hu was used for /ʁʷ/, similar to French roi. The sequence hu is also found in Spanish words such as huevo or hueso; however, in Spanish this is not a digraph but a simple sequence of silent h and the vowel u.

〈hv〉 is used Faroese and Icelandic for /kv/ (often /kf/), generally in wh-words, but also in other words, such as Faroese hvonn. In the General Alphabet of Cameroon Languages it is used for the supposed fricative /ɣ͜β/.

〈hw〉 is used in modern editions of Old English for /hw/, originally spelled 〈huu〉 or 〈hƿ〉 (the latter with the wynn letter). In its descendants in modern English, it is now spelled 〈wh〉 (see there for more details). It is used in some orthographies of Cornish for /ʍ/.[4][5]

〈hx〉 is used in Pinyin for /h/ in languages such as Yi (〈h〉 alone represents the fricative /x/), and in Nambikwara it is a glottalized /hʔ/. In Esperanto orthography, it is an unofficial surrogate of 〈ĥ〉, which represents /x/.

〈jh〉 is used in Walloon to write a sound that is variously /h/ or /ʒ/, depending on the dialect. In Tongyong pinyin, it represents /tʂ/, written zh in standard pinyin. Jh is also the standard transliteration for the Devanāgarī letter झ /dʒʱ/. In Esperanto orthography, it is an official surrogate of 〈ĵ〉, which represents /ʒ/.

〈kh〉, in transcriptions of Indo-Aryan and Dravidian languages, represents the aspirated voiceless velar plosive (/kʰ/). For most other languages ,[better source needed] it represents the voiceless velar fricative /x/, for example in transcriptions of the letter ḫāʾ (خ) in standard Arabic, standard Persian, and Urdu, Cyrillic Х, х (kha), Spanish j, as well as the Hebrew letter kaf ( כ) in instances when it is lenited. When used for transcription of the letter ḥet (ח) in Sephardic Hebrew, it represents the voiceless pharyngeal fricative /ħ/. In Canadian Tlingit it represents /qʰ/, which in Alaska is written k. In the Ossete Latin alphabet, it was used for /kʼ/.

〈lh〉, in Occitan, Gallo, and Portuguese, represents a palatal lateral approximant /ʎ/. In many Indigenous languages of the Americas it represents a voiceless alveolar lateral fricative /ɬ/. In the transcription of Australian Aboriginal languages it represents a dental lateral, /l̪/. In the Gwoyeu Romatzyh romanization of Mandarin Chinese, initial 〈lh〉 indicates an even tone on a syllable beginning in /l/, which is otherwise spelled 〈l〉. In Middle Welsh it was sometimes used to represent the sound /ɬ/ as well as 〈ll〉, in modern Welsh it has been replaced by 〈ll〉. In Tibetan, it represents the voiceless alveolar lateral approximant, as in Lhasa.

〈mh〉, in Irish, stands for the lenition of 〈m〉 and represents /v/ or /w/; for example mo mháthair /mə ˈwɑːhəɾʲ/ or /mˠə ˈvˠɑːhəɾʲ/ "my mother" (cf. máthair /ˈmˠɑːhəɾʲ/ "mother"). In Welsh it stands for the nasal mutation of 〈p〉 and represents /m̥/; for example fy mhen /və m̥ɛn/ "my head" (cf. pen /pɛn/ "head"). In both languages it is considered a sequence of the two letters 〈m〉 and 〈h〉 for purposes of alphabetization. In Shona, Juǀʼhoan and several other languages, it is used for a murmured /m̤/. In the Gwoyeu Romatzyh romanization of Mandarin Chinese, initial mh- indicates an even tone on a syllable beginning in /m/, which is otherwise spelled m-. In several languages, such as Gogo, it's a voiceless /m̥/.

〈ng〉, in Sino-Tibetan languages, [8] as in English and several other European and derived orthographies (for example Vietnamese), [9] generally represents the velar nasal /ŋ/. [10] [11] [UKT ¶ ]

UKT 200909: The present concept of "Sino-Tibetan" is a disservice to Tibeto-Burman language group to which my mother tongue Bur-Myan belongs. Myanmar script - based on perfect circles - is unique in the world. The only script that comes closest to it is the Mkhedruli script in which Georgian speech is written. Including Bur-Myan in Sino-Tibetan obscures this fact.

〈ng〉 is used to represent Bur-Myan

{gna.}/

{ng} which is non-nasal in the onset of a syllable, and nasal in the coda. I'm using the term semi-nasal for it.

It is considered a single letter in many

Austronesian languages (Māori,

Tagalog,

Tongan,

Gilbertese,

Tuvaluan,

Indonesian,

Chamorro),[12]

the

Welsh language, and

Rheinische Dokumenta, for

velar nasal

/ŋ/; and in some

African languages (Lingala,

Bambara,

Wolof) for

prenasalized

/ɡ/

(/ⁿɡ/).[13][14]

For the development of the pronunciation of this digraph in English, see

NG-coalescence and

G-dropping.

The

Finnish language uses the digraph 'ng' to denote the phonemically long

velar nasal

/ŋː/ in contrast to 'nk'

/ŋk/, which is its "strong" form under

consonant gradation, a type of

lenition.

Weakening

/k/ produces an

archiphonemic "velar fricative", which, as a velar fricative does not exist

in Standard Finnish, is assimilated to the preceding

/ŋ/, producing

/ŋː/. (No

/ɡ/ is involved at any point, despite the spelling 'ng'.) The digraph 'ng'

is not an independent letter, but it is an exception to the

phonemic principle, one of the few in standard Finnish.

In

Irish ng is used word-initially as the

eclipsis of g and represents

/ŋ/, e.g. ár ngalar

/ɑːɾˠ ˈŋɑɫəɾˠ/ "our illness" (cf.

/ˈɡɑɫəɾˠ/). In this function it is capitalized nG, e.g. i

nGaillimh "in Galway".

In Tagalog and other

Philippine languages, ng represented the prenasalized sequence

/ŋɡ/ during the Spanish era. The velar nasal,

/ŋ/, was written in a variety of ways, namely "n͠g", "ñg", "gñ" (as in

Sagñay), and—after a vowel—at times "g̃". During the standardization of

Tagalog in the early part of the 20th century, ng became used for the

velar nasal

/ŋ/, while prenasalized

/ŋɡ/ came to be written

ngg. Furthermore, ng is also used for a common

genitive particle pronounced

/naŋ/, to differentiate it from an adverbial particle nang.

In

Uzbek, it is considered as a separate letter, being the last (twenty-ninth)

letter of the

Uzbek alphabet. It is followed by the

apostrophe

(tutuq belgisi).

〈ńg〉 is used in Central Alaskan Yup'ik to write the voiceless nasal sound /ŋ̊/.

〈ñg〉, or more precisely 〈n͠g〉, was a digraph in several Spanish-derived orthographies of the Pacific, such as that of Tagalog[15] and Chamorro,[16] where it represented the sound /ŋ/, as opposed to ng, which originally represented /ŋɡ/. An example is Chamorro agan͠gñáijon (modern agangñaihon) "to declare". Besides ñg, variants of n͠g include gñ (as in Sagñay), ng̃, and a g̃, that is preceded by a vowel (but not a consonant). It has since been replaced by the trigraph 〈ngg〉 or 〈ng〉 (see above).

〈ngʼ〉 is used for /ŋ/ in Swahili and languages with Swahili-based orthographies. Since 〈ʼ〉 is not a letter in Swahili, 〈ngʼ〉 is technically a digraph, not a trigraph.

〈nh〉 is used in several languages. See article.

〈ph〉, in English and some other languages, represents /f/, mostly in words derived from Greek. The Ancient Greek letter phi 〈Φ, φ〉 originally represented /pʰ/ (an aspirated p sound), and was thus transcribed into Latin orthography as 〈PH〉, a convention that was transferred to some other Western European languages. The Greek pronunciation of 〈φ〉 later changed to /f/, and this was also the sound adopted in other languages for the relevant loanwords. Exceptionally, in English, 〈ph〉 represents /v/ in the name Stephen and some speakers' pronunciations of nephew.

〈qh〉 is used in various alphabets. In Quechua and the Romanized Popular Alphabet used to write Hmong, it represents the sound /qʰ/. In Xhosa, it represents the click /ǃʰ/.

〈rh〉 is found in English language with words from the Greek language and transliterated through the Latin language. Examples include "rhapsody", "rhetoric" and "rhythm". These were pronounced in Ancient Greek with a voiceless "r" sound, /r̥/, as in Old English 〈hr〉. The digraph may also be found within words, but always at the start of a word component, e.g., "polyrhythmic". German, French, and the auxiliary language Interlingua use rh in the same way. 〈Rh〉 is also found in the Welsh language where it represents a voiceless alveolar trill (r̥), that is a voiceless "r" sound. It can be found anywhere; the most common occurrence in the English language from Welsh is in the slightly respelled given name "Rhonda". In Wade-Giles transliteration, 〈rh〉 is used for the syllable-final rhotic of Mandarin Chinese. In the Gwoyeu Romatzyh romanization of Mandarin Chinese, initial rh- indicates an even tone on a syllable beginning in /ʐ/, which is otherwise spelled r-. In Purépecha, it is a retroflex flap, /ɽ/.

〈sh〉 is used in several languages. In English, it represents /ʃ/. See separate article. See also ſh below, which has the capitalized forms SH and ŞH.

〈vh〉 represents /v/ in the Shona language. It was also used in the Tindall orthography of Khoekhoe for the aspirated palatal click /ǂʰ/.

〈wh〉 is used in English to represent Proto-Germanic /hw/, the continuation of the PIE labiovelar */kʷ/ (which became 〈qu〉 in Latin and the Romance languages). Most English question words begin with this digraph, hence the terms wh-word and wh-question. In Old English, /hw/ was spelled 〈huu〉 or 〈hƿ〉, and only the former was retained during the Middle English period, becoming 〈hw〉 during the gradual development of the letter 〈w〉 during the 14th-17th centuries. In most dialects it is now pronounced /w/, but a distinct pronunciation realized as a voiceless w sound, [ʍ], is retained in some areas: Scotland, central and southern Ireland, the southeastern United States, and (mostly among older speakers) in New Zealand. In a few words (who, whole, etc.) the pronunciation used among almost all speakers regardless of geography is /h/. For details, see Pronunciation of English 〈wh〉. In the Māori language, 〈wh〉 represents /ɸ/ or more commonly /f/, with some regional variations approaching /h/ or /hw/. In the Taranaki region, for some speakers, this represents aglottalized /wʼ/. In Xhosa, it represents /w̤/, a murmured variant of /w/ found in loan words. In Cornish, it represents /ʍ/.[1][3][5]

〈xh〉, in Albanian, represents the sound of the voiced postalveolar affricate consonant /dʒ/, as in the surname Hoxha /ˈhɔdʒa/. In Zulu and Xhosa it represents the voiceless aspirated alveolar lateral click /kǁʰ/, for example in the name of the language Xhosa /ˈkǁʰoːsa/. In Walloon to write a sound that is variously /h/ or /ʃ/, depending on the dialect. In Canadian Tlingit it represents /χ/, which in Alaska is written x̱.

〈yh〉 was used in the pre-1985 orthography of Guinea, for the "ejective y" or palatalized glottal stop (/ʔʲ/) in Pular (a Fula language). In the current orthography it is now written ƴ. In Xhosa it is used for the sound / j̈ /. In a handful of Australian languages, it represents a "dental semivowel".[clarification needed]

〈zh〉 represents the voiced postalveolar fricative (/ʒ/), like the 〈s〉 in pleasure, in Albanian and in Native American orthographies such as Navajo. It is used for the same sound in some English-language dictionaries, as well as to transliterate the sound when represented by Cyrillic 〈ж〉 and Persian 〈ژ〉 into English; though it is rarely used for this sound in English words (perhaps the only one being zhoosh). 〈Zh〉 as a digraph is rare in European languages using the Latin alphabet; in addition to Albanian it is found in Breton in words that are pronounced with /z/ in some dialects and /h/ in others. In Hanyu Pinyin, 〈zh〉 represents the voiceless retroflex affricate /tʂ/. When the Tamil language is transliterated into the Latin script, 〈zh〉 represents a retroflex approximant (Tamil ழ U+0BB4, ḻ, [ɻ]).

〈ŋg〉 is used in the General Alphabet of Cameroon Languages for /ŋɡ/.

〈ŋk〉 is used in the General Alphabet of Cameroon Languages for /ŋk/.

〈ŋm〉 is used in the General Alphabet of Cameroon Languages for the labial-velar nasal /ŋ͡m/.

〈ŋv〉, capitalized 〈Ŋv〉, was used for /ŋʷ/ in the old orthography of Zhuang and Bouyei; this is now spelled with the trigraph 〈ngv〉.

〈ſh〉, capitalized 〈SH〉 or sometimes 〈ŞH〉, was a digraph used in the Slovene Bohorič alphabet for /ʃ/. The first element, 〈ſ〉, the long s, is an archaic non-final form of the letter 〈s〉.

Go back Latin-digraphs-note-b

End of TIL file